Model transitions: A framework for value creation

And a quick and dirty look at SPLK, NTNX, and GWRE

This week I was going to write about what I call the “science of SaaS” or how, as a management team, to plan and measure outcomes for a SaaS business. But, I’m going to deviate from that plan because it is a meaty topic and I haven’t yet figured out how to boil it down into something easy to read.

Instead, I’m going dive into a question from one of my readers. The reader asked about Splunk and its model transition. Rather than provide detailed company specific thoughts (I don’t have conviction yet either way), I thought instead I’d outline my framework for evaluating model transitions.

The model transition opportunity

In the last decade, model transitions have usually meant shifting from selling licenses to selling subscriptions. Typically some sort of on-prem to cloud migration also is occurring.

Model transitions are a great source of value creation for investors and management teams. For a management team, undertaking a model transition forces your company to accelerate modernization. By disrupting your legacy economic model, you are forcing change upon your organization. Inertia is powerful (especially in larger companies), so a radical change to how the company makes money can be an effective way to rally the troops and accelerate a future proofing effort. Subscription models also tend to garner a higher multiple, leading to a double re-rating: future proofing plus subscription model uplift. As an example, ADSK has rerated from a mid-single digit EV/NTM sales multiple to a mid-teens EV/sales multiple over the last 5 years.

For investors, you can potentially reap the benefit of the above value creation plus the the uncertainty created by the transition. Model transitions disrupt the income statement, making the business harder to evaluate for both active and passive investors. Flows tend to lag inflection points because of this.

Metrics to track during model transitions

While model transitions create opportunity, they also create significant execution risk. A company must rebuild, repackage and reprice its products. It must change sales and channel compensation plans. And it has to effectively communicate what it is doing to investors to avoid the stock getting crushed as revenue decelerates and margins compress. Because of this, model transitions often get put in the “too hard” basket by investors.

I’ve come across a lot of ways to evaluate model transitions. Some investors will build incredibly complex models that do things like convert licenses to subscriptions to try to get a sense of “true” underlying growth. But I try to keep it relatively simple and primarily track two metrics:

Growth in incremental ARR (annual recurring revenue) - During a model transition it has become best practice to disclose annual recurring revenue or an ARR equivalent. Current quarter ARR - year ago quarter ARR = incremental ARR.

Run-rate margins - Run rate expenses are current quarter (subscription COGS+Operating Expenses)*4. Run-rate margins are (ARR-run rate expenses)/ARR.

Model transition stocks tend to work on improving trends in the above.

Incremental ARR: Growth required

During most model transitions, two mix shifts are happening:

a new business mix shift where a growing percentage of new and expansion dollars are being sold as subscriptions.

a renewal base mix shift, where existing customers are moving from a license model to a subscription model, often in conjunction with a move from a legacy on prem product to a subscription product

Both of these should be a tailwind to incremental ARR growth. But, model transitions are also messy and take some time for management teams to figure out. The cloud product is immature. Some customers don’t want to migrate. Others may want to buy using a perpetual license models. Sales incentives are set too high or too low. Its fucking messy. And while the company is navigating this messiness, it has to develop the product, build the brand, generate leads, and win against the competition. You know, normal business building stuff.

Despite this, investors tend to view deteriorating trends in incremental ARR as a sign that something more ominous is occurring. ADSK has had multiple double-digit sell-offs over the years largely for this reason. SPLK has as well. Because of this, transition stocks don’t tend to work unless growth in incremental ARR is stable to improving.

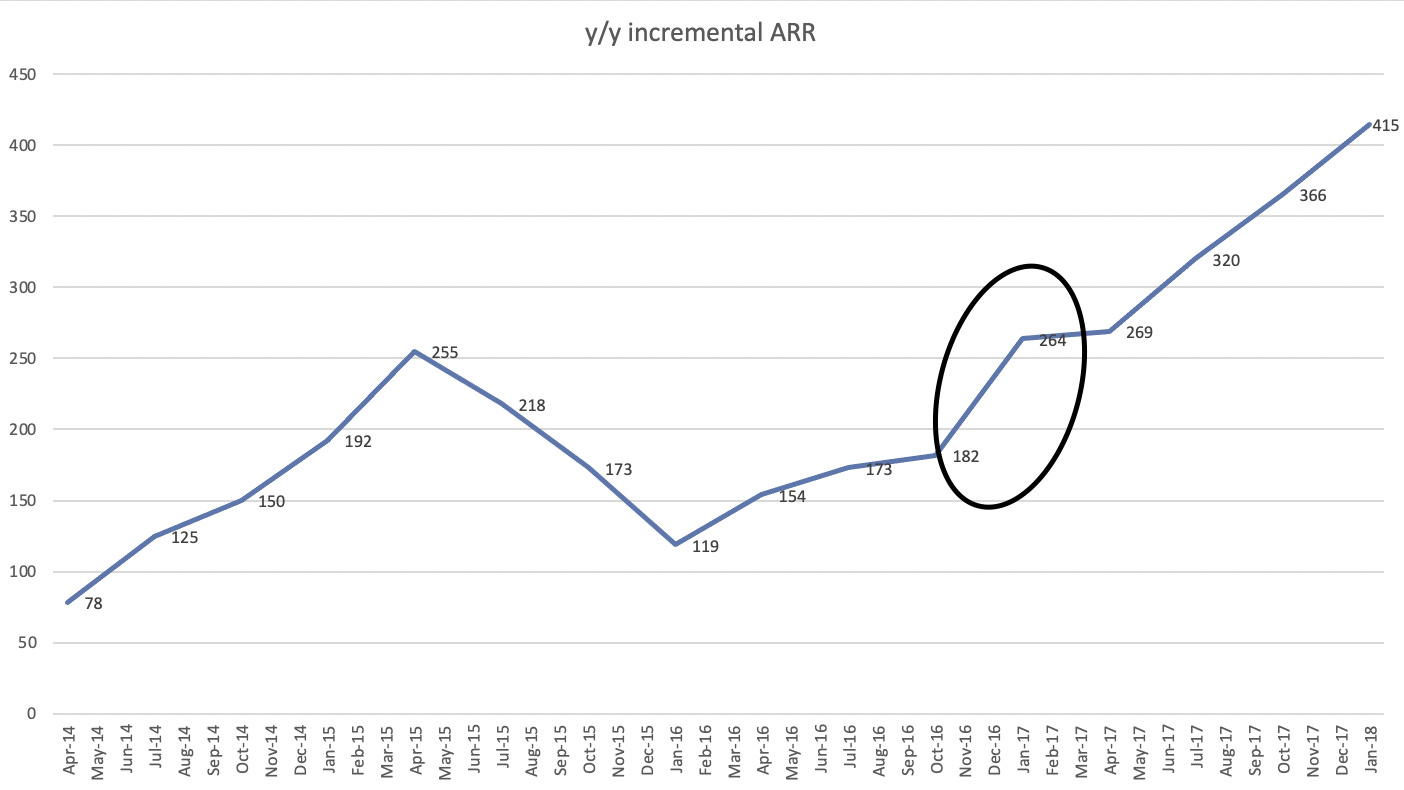

Autodesk is a good example here. The company had some hiccups with its model transition leading to declining incremental ARR growth in the second half of CY15 and the first half of CY16. The stock significantly underperformed the IGV. In late CY16 for various reasons incremental ARR (black circle) started to grow again and the stock proceeded to moon over the next few quarters.

You did not have to bottom-tick to do well here. You did not even have to buy at the first sign of year-over-year growth (fall of CY16). You just had to realize that a couple of years into its model transition, management had finally rebuilt the machine and it was running smooth enough to drive sustainable growth in the incremental. In other words, Autodesk had sorted through the messiness and the business was starting to hum.

Run-Rate Margins: Looking for breakeven

Top-line typically matters most for a software business. But, the cost structure has to make sense. If a company is spending too much to grow incremental ARR then the stock probably won’t work because terminal margins are unclear.

Additionally, it is hard for a model transition stock to work if the transition drags on for a long time. Investors need some light at the end of the tunnel. Multiple years of low revenue growth and limited margin expansion are just not compelling.

So the other metric I like to look at is run-rate margins. Run-rate margins are helpful for two reasons: first, they give you an easy way to sense if the economics of the model transition are working and second, they are an easy proxy of what inning the model transition is in.

The first thing I’m looking for is when run-rate margins turn positive. Effectively this means the ARR base can support the cost structure of the business. And if incremental ARR is growing that usually means multiple quarters or years of margin expansion are about to occur. I’ll use Dynatrace as an example here.

For DT, once run-rate margins were at breakeven reported operating margins inflected. Eventually run-rate margins exceeded operating margins due to an income statement drag from lower license revenues and low professional services gross margins. ADSK had a very similar trajectory.

Now, as a caveat this is all much easier to analyze after the fact. In the moment, management teams are sandbagging, there is doubt about what incremental ARR is going to do in the forward quarters, etc.

SPLK, NTNX, and GWRE: Evaluating model transitions

Ok, with that context let’s look at some model transitions where there is still doubt. SPLK, NTNX and GWRE have all significantly underperformed the IGV over the last two years. This is largely due to complex model transitions that have created debate about the true trajectory of each business and what terminal margins might look like.

First, on the incremental ARR front, none of these businesses is humming along. SPLK is growing the incremental, but it has been rockier over the last year. NTNX and GWRE are roughly flat. However, it is important to note that none of these businesses are WFH beneficiaries and likely faced more headwinds than tailwinds over the last year due to tighter budgets and elongated sales cycles.

For run rate margins, SPLK is very close to breaking even. GWRE run rate margins are positive but declining! NTNX is improving, but still likely multiple quarters from breakeven.

Putting these together, below is how I’m thinking about each:

GWRE is still figuring things out. Will wait and see even though I like the vertical-specific nature of the business.

NTNX needs to right size its cost structure. The incremental has not grown for multiple years and value creation for shareholders is likely to come from margin expansion vs growth. Maybe the new CEO takes this approach (he likely needs a new operationally-excellent CFO to partner with on this strategy).

SPLK looks interesting. The incremental continues to grow and run-rate margins are about to breakeven. I’m going to do more work here.

What is run rate margin and how do you calculate it ?

When looking at y/y incremental ARR for ADSK, which numbers do you use? Subscription plan ARR, Total ARR (I am looking at Q4'18, maybe these metrics go by other names now) or anything else? I cant get the numbers to work when comparing actual numbers and numbers in your figure. Thanks.