The Wrong Bet

The next decade in SaaS won't look like the last

“Value investing is betting the world is going to stay the same. Venture capital is betting the world will be different.”

You’ve probably seen something like the above quote floating around. I like it. But, as I heard about another private SaaS deal priced at 80x ARR I couldn’t help but reframe it:

“What happens when venture investors bet the world is going to stay the same?”

That is what is happening in SaaS right now. The market is pricing the future like the past.

The abundance era

In the early part of the 2010s the following market conditions existed for cloud:

Digitization was a major secular tailwind

Market penetration was near zero

The competitor was on-premise software

Incumbent mega-vendors in enterprise technology were slow to adapt

The cost of capital was still relatively high

These conditions were extremely beneficial to vendors such as ServiceNow, Workday, Salesforce, Veeva, Netsuite and of course AWS. The market was effectively greenfield for cloud and the counter-positioning against legacy on-prem providers was crystal clear and very compelling: you can modernize and save money. In many cases SaaS would save customers 2-3x over a decade vs on prem competitors due to lower hardware, services, and headcount costs. ServiceNow built its entire business on replacing BMC Remedy with the above pitch.

Mega-vendors primarily tried to compete and buy time via aggressive discounting, vaporware marketing, and sales/contracting tactics. It wasn’t until the middle of the decade that SAP, Oracle and Microsoft hit the gas on the technology and business model transformation necessary to compete for the long run.

Competition from new entrants was also limited due to the financial crisis. The cost of capital was very high from the 2008-2012 period. You could raise money if you had traction, but the mega-rounds of today were non-existent. Workday’s Series F in 2011 was only $85M. Zendesk raised $60M in its 2012 Series D. Hubspot raised a $35M Series E the same year.

The market conditions were a dream for early movers and oligopolies formed in large core/sticky markets, leading to high retention and high incremental margins.

The sharp elbows era

Market conditions have changed substantially over the last decade:

Digitization is still a major secular tailwind

Market penetration is rapidly approaching the mid-double digits

The competitor is other SaaS/cloud companies

Mega-vendors are hyper aggressive

The cost of capital is the lowest it has ever been

There remains a massive secular tailwind to the industry. Businesses are investing heavily to digitize. Software is an outsized beneficiary from this investment. Software spend as a % of GDP is likely to increase every year for the next couple of decades.

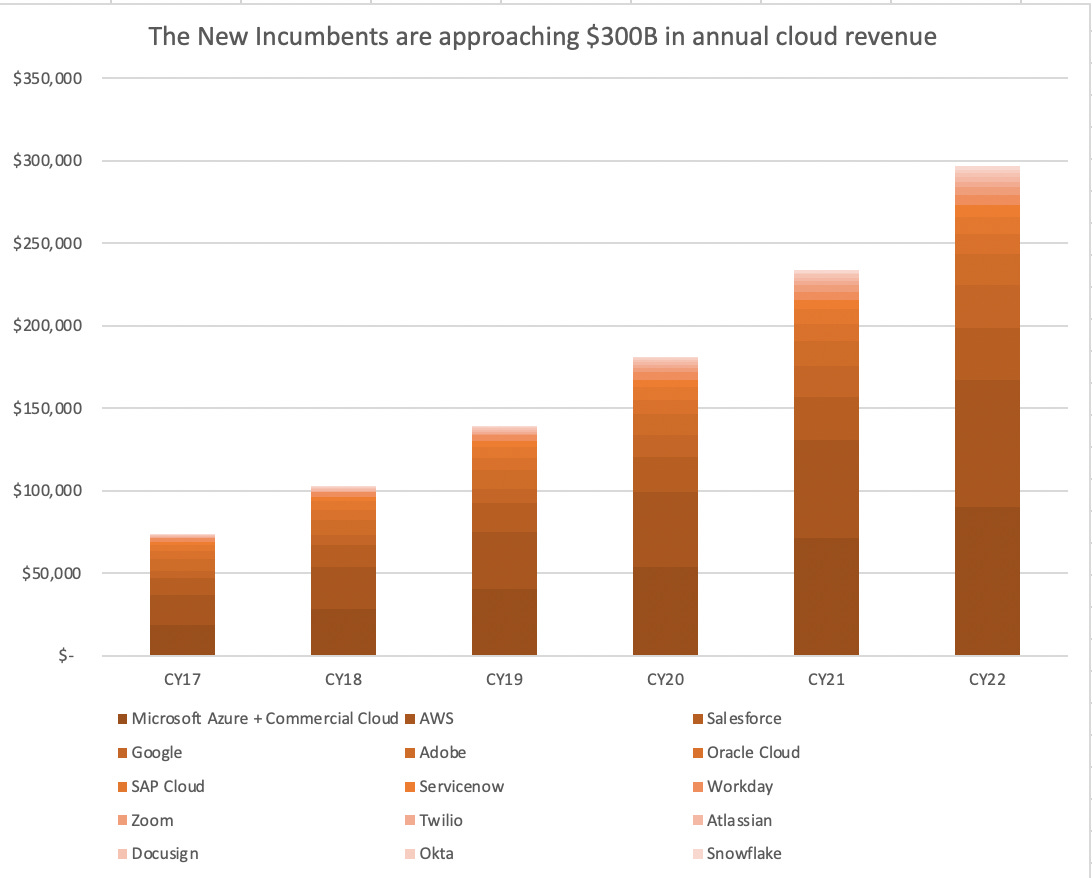

But cloud is substantially more penetrated than it was a decade ago. A group of 15 vendors that I’ve lamely dubbed the “new incumbents” are likely to approach or exceed $300B of annual cloud revenue by 2022, up nearly 10x from 2015. Gartner pegs the total software + hardware market at about $700B in CY22. So cloud is approaching 50% of total spend.

It will likely eventually be 90%+ of spend, but growth is likely to start slowing as penetration exceeds 50%. And, while the software pie will grow as companies invest in productivity, there is a limit to how fast IT budgets can grow.

A less attractive market structure for investors

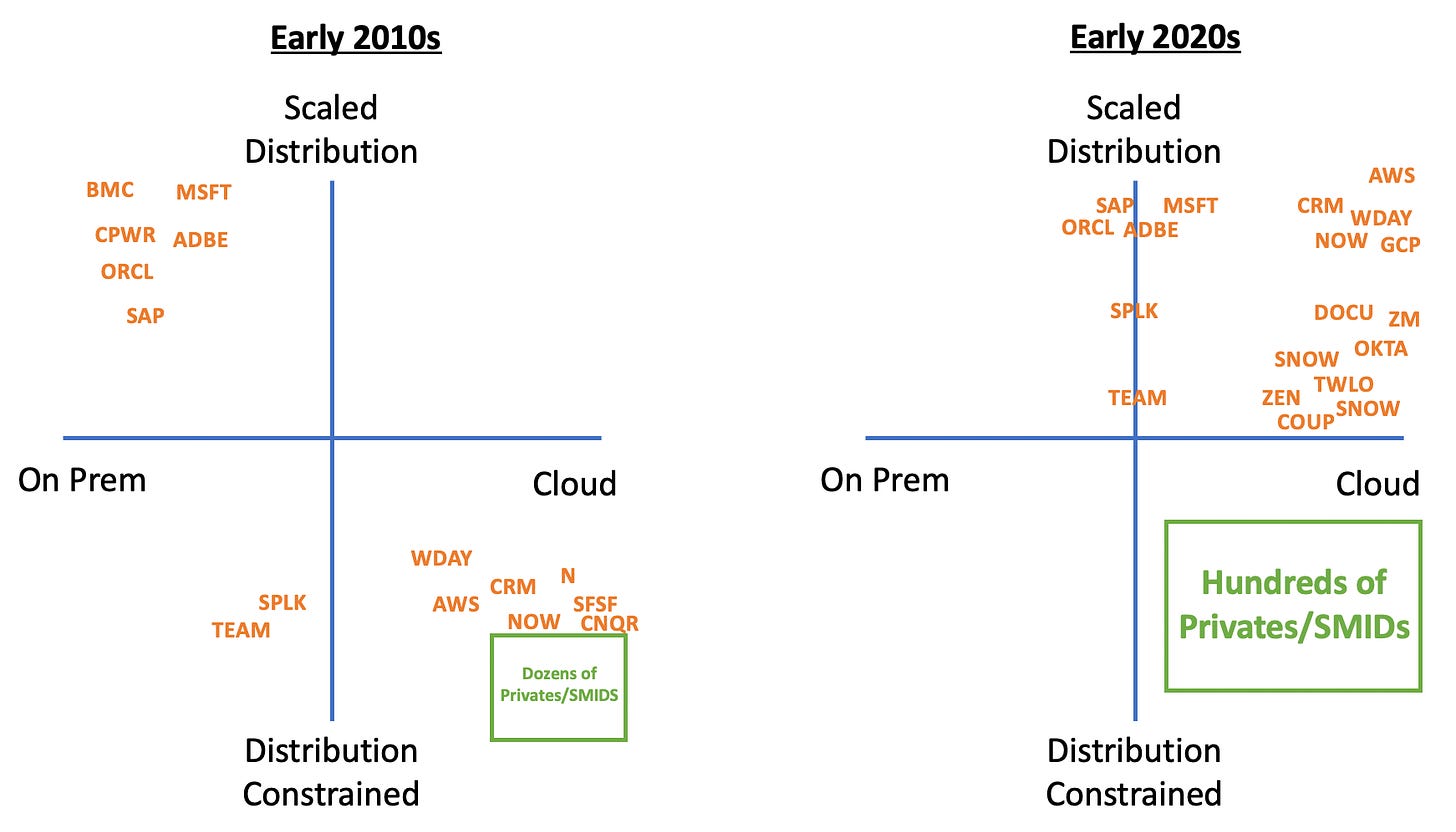

When the cloud boom started, there were three types of market participants: 1) incumbents without the technology but with the distribution, 2) disruptors with the technology but without the distribution, 3) future private equity acquisitions. Today there are two types of competitors: 1) incumbents with the distribution and technology and 2) new entrants with the technology, but without enterprise distribution.

This is a much less shareholder friendly market structure! Scaled, well-capitalized and well-run incumbents are increasingly competing against one another to sustain growth versus competing against on prem share donors. This means elevated M&A, elevated R&D spend, and elevated S&M spend to achieve the same level of growth.

The cost of capital for new entrants is also very low. Hopin, an event software company, just raised $400M in its series C. Databricks, a cloud-based data platform, recently raised $1B in its Series G. Airtable raised $270M in a Series E. Contrast these rounds to the size of the rounds in the early part of the last decade. All of these companies are competing directly against other cloud vendors for customers and talent.

Many new entrants are doing well. The market is large and the early adopter (tech and media companies) budget pool is substantially larger than 10 years ago. In some cases, new categories are being created that justify new budget. But, the cost to grow is higher. And given the new market structure, the cost to sustain growth in the future will also likely be substantially higher.

In some ways, the current market dynamics in software remind me of semiconductors from 2000-2015. Enabling technologies (ARM, design software) and low cost of capital in the late 1990s enabled rapid growth in the number of competitors. This led to subpar returns for the industry despite a very large and obvious secular tailwind (more compute). Software is a better business model than semiconductors and much less cyclical, but there are parallels from a market structure perspective.

Pricing growth based on the past, rather than the future

To summarize, the market has evolved from extremely attractive (secular tailwind, low penetration, limited competition, high incremental margins) to somewhat attractive (secular tailwind, medium penetration, more competition, lower incremental margins). But multiples are moving substantially higher. Why?

There are undoubtedly VC industry dynamics at play. Investors that made a lot of money on SaaS over the last decade have raised new funds and have to put the money to work. And there will undoubtedly be some big winners. The new incumbents will need to do M&A to sustain growth, so that will drive some return.

But, the logic justifying capital deployment at these multiples seems broken. Many investors seem to be taking the market growth of the last decade, extrapolating that forward, and using more mature market leaders like NOW, VEEV, and ADBE as comparables to derive terminal margins and terminal multiples. This is despite higher market penetration, more competition, lower incremental margins, and the likelihood of higher spend at maturity to remain competitive.

In other words, rather than betting that things will change growth investors are betting that things will remain the same.

SNOW's so good you have it twice in your graph!

The Global IT budget is 4T/year, less 20% is on cloud (700bn, the figure in your research), do you think the cloud (software + hardware) will gain more shares in the IT budget? from 20% to 50% in the next 10-15 years? then it will enlarge the market significantly? Thanks